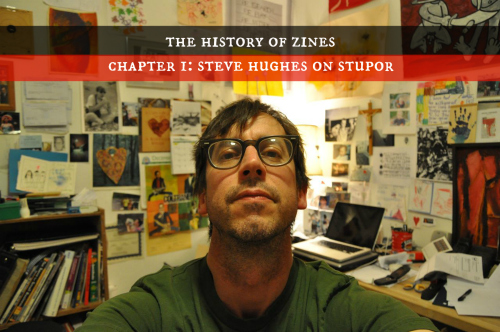

Over the years I’ve mentioned my friend Steve Hughes and his zine Stupor several times on this site. I’ve shared videos of him reading at the Shadow Art Fair, and interviewed him about his various projects in Hamtramck, where he makes his home and runs an art space called Public Pool. To my knowledge, though, I’ve never asked him how he got his start. I’ve never asked him why it was, as a young man, that he first waded out into the murky waters of self-publishing, or, for that matter, what he’s learned from the experience. Well, in hopes of answering these questions and more, I’ve spent the past few days exchanging calls and emails with Steve, resulting in the following. My hope is that it’s the first of many such interviews with those individuals who, like Steve, helped create the American zine movement… Enjoy.

MARK: I can’t remember how we first crossed paths. In spite of the fact that I used to play in bands in Ann Arbor at the same time as your brother, in the early 90s, I don’t think you and I became aware of one another until years later, when you were living in New Orleans and I was living in Atlanta. And, even then, I don’t think Greg had anything to do with our meeting. I think either you or I probably just read a review in Factsheet Five, sent a letter, and initiated a trade… Is that how you remember it?

STEVE: Shoot, I don’t remember how it started. Factsheet 5 probably played a role. It was an amazing resource for connecting other with zine writers.

MARK: How would you describe Stupor, for folks in the audience who may not have ever seen an issue?

STEVE: Stupor is a collection of true stories that I build by talking to people at bars. We drink, and they talk about their lives, and I listen. Later, I write it all down, doing my best to get it right. I then work with an artist who accomplishes the layout for each issue. In recent Stupors, I’ve been using themes to better connect with my collaborating artist. For example, when I was working with Matthew Barney (the Cremaster), I gathered stories about cars and blood and mud.

MARK: How’d you come to know Matthew Barney, and ask him to collaborate?

STEVE: I worked on a film he was making in Detroit. I did landscaping for him. It was cool. I bought a machete and used that to hack up a lot of weeds and scrub. We were clearing land out near Zug Island. We cut trees too and did some digging as well, which was weird. The land out there is made of rust and poison.

MARK: Was it at all awkward, asking him to collaborate? [note: Barney cover to right.]

MARK: Was it at all awkward, asking him to collaborate? [note: Barney cover to right.]

STEVE: Before I asked him to lay out a Stupor, I asked him if he’d consider writing a blurb for my book. He was real cool about agreeing to do that. Then, after it printed, I sent him a couple copies and asked what he thought about it. He said that he “psyched” to be involved. For sure, I was psyched that he was psyched. After that I got it in my head that he might also be interested in doing layout of his own for a new issue. So I asked and he said sure. It was never awkward. He’s a very personable guy.

MARK: Was Stupor your first publication, or had there been others before it?

STEVE: Stupor was the first.

MARK: Do you recall how the idea for Stupor first came to you?

STEVE: It wasn’t my idea. The spark came from my friend Bill Rohde. We had both read a book by Dennis Cooper called Try

MARK: What’s Bill up to these days?

STEVE: After we left New Orleans he moved to Gary, Indiana and started driving trucks, the big rigs. Later, I think he worked dispatch and then desk job, and now I’m pretty sure he’s corporate, probably all for the same company. Trucking.

MARK: Do you think he’s happy about the success you’ve had with Stupor?

MARK: Do you think he’s happy about the success you’ve had with Stupor?

STEVE: I don’t see why he wouldn’t be. It was his idea, but not his thing. I mean he didn’t want to continue and I did, and then it became something different anyway. I know this: he’s really smart and a great writer, and I owe him a huge thanks for coming up with the idea and the desire to do a zine. I probably wouldn’t have if it wasn’t for him.

MARK: So Stupor started out as a compilation of personal, twisted stories from fellow aspiring writers… How’d you then make the jump to soliciting stories from regular folks at the bar?

STEVE: After I moved to Detroit, my days of free printing were over, and I was broke. Although I like what Stupor had become, it didn’t make sense to keep publishing my friend’s stuff. So I came up with the idea of collecting stories from people I didn’t know at bars but writing them myself. For one, I love bars and I like talking and it seems that everybody’s got a story. Turns out it was easy to get them to open up and talk. So I started doing theme based issues, and I’d tell whoever that I was talking to what I was working on and they’d start telling me the craziest stuff.

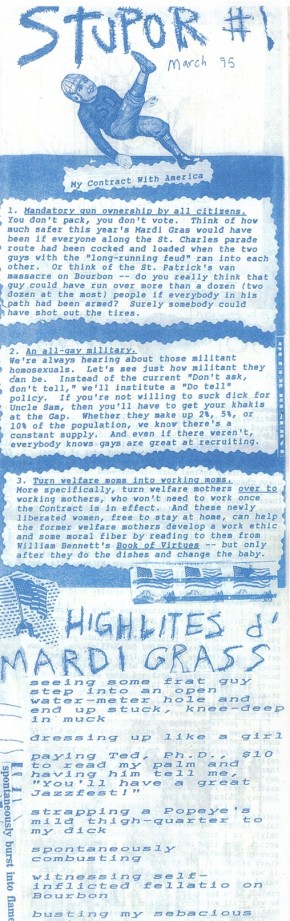

MARK: Help me out with the Stupor timeline. What year did the first issue come out, and what were you doing at the time?

MARK: Help me out with the Stupor timeline. What year did the first issue come out, and what were you doing at the time?

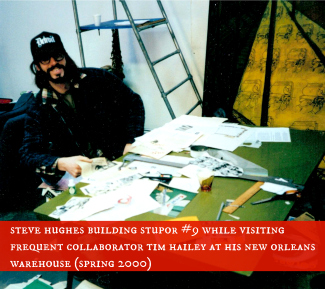

STEVE: Issue #1 happened in New Orleans, maybe February or March of 1995. Probably right after Mardi Gras. We then did three more issues in quick succession. I think we wanted it to be monthly. This didn’t last long. So when issue #1 came out I was in grad school. I was just finishing my thesis work. After about three years of intensive writer’s workshops, I was pretty blown out. Stupor happened at a good time. Suddenly I had an outlet for whatever I wanted to write. Not only that but I had an audience, and celebrity too. Yeah, that happened. That was kind of cool. “Oh, you’re that guy that does Stupor? I’ve got all the issues sitting on the back of my toilet. I love it.” It was great hearing stuff like that. So Stupor started in a quick burst and after about five months and four issues, I left New Orleans and moved to Hamtramck, and my pace slowed.

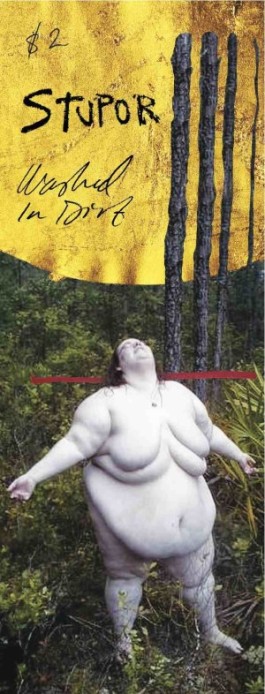

MARK: You mention toilet tanks… Stupor, for those who have never seen a copy, is long and slender. The perfect size for a toilet tank… Was that by design? Did you know from the outset that Stupor would be something read while using the toilet, and design it like that on purpose?

STEVE: There wasn’t an intentional connection, but it didn’t take me long to realize how perfectly they fit on a toilet tank. Especially the older issues which were 17 inches long. Plus I’ve always appreciated a story that’s short enough to be read in one brief sitting or visit to the john.

MARK: How would you characterize your childhood?

STEVE: I had a good childhood. My family was intact, and I had a brother and sister to fight with. I played with Planet of the Apes action figures and listened to music on the AM radio. So, mostly I’d say it was normal. I didn’t do weird things like torture animals or anything. I liked to climb trees and play with pillbugs. I read Mad magazine and collected coins and learned to shoot a gun and fish too.

MARK: You had, if I recall correctly, gone to Hope College out of high school, which is a small Christian college, right? Were you already writing at that point? And, if so, what kind of stuff were you writing?

STEVE: It is a Christian college. That’s true. And that was definitely part of why I went there. I was into youth group, bible study and all that. It used to embarrass me to say so, even years later. I don’t know why. It was just who I was at the time, and part of why I am who I am now, too. But yeah, I was writing in high school and then at Hope College too. They had a couple good writers working there in the English Department. Back then, I had the idea that I was a good poet and that I was going to make it as either a writer or an artist or a musician, like some sort of fame was going to descend on me. Some talent scout would discover me. Put me on TV or something.

MARK: While I wouldn’t describe the content of Stupor as being un-Christian, it can sometimes be a little on the dark side… certainly not something I would imagine being stocked in the Hope College library… and I was wondering when that side of you emerged. Was it always there, or did an appreciation for the underbelly of society kind of evolve over time?

MARK: While I wouldn’t describe the content of Stupor as being un-Christian, it can sometimes be a little on the dark side… certainly not something I would imagine being stocked in the Hope College library… and I was wondering when that side of you emerged. Was it always there, or did an appreciation for the underbelly of society kind of evolve over time?

STEVE: That’s hard to know. I mean, at some point I quit doing the church stuff, but I don’t think I turned bad. You’re right though, I sure appreciate the raw and real grit of the world.

MARK: What had taken you to New Orleans?

STEVE: I got into a writer’s workshop at the University of New Orleans. It was a pretty good deal. Very cheap. Also I loved the city and thought it would be great to live there. It was.

MARK: So what brought you back to Michigan?

STEVE: My wife got into a masters program at Wayne State. They gave her a pretty good offer.

MARK: And, when was it that you were at Eastern Michigan University, working with Janet Kauffman? …How did your writing change during that period?

STEVE: I took those classes with Janet back in the early 90s. So it was between college and grad school. She was a great mentor, super smart and engaged. She appreciated the fray of energy in me that I couldn’t quite make sense of. I was trying though. She gave me some good direction. She remains my all time favorite.

MARK: Were you aware of so-called “zine culture” when you published that first issue of Stupor? Did you know that there was the network of weirdos trading self-published magazines through the mail?

STEVE: I had no idea what I was getting into when I first started. Soon after starting Stupor, I was sending issues to prisoners, and getting all sorts of great stuff in the mail. It was stunning. I mean that this world was out there. And then suddenly I was part of it too. I was one of those weirdos. I’ve met some great people through it. I still keep up with some of them. Notably you and Linette, my good friend Michael Jackman from Inspector 18, and Lisa Anne Auerbach who did Snowflake and American Homebody.

MARK: Where did you print your first issue?

STEVE: Kinkos, of course. Bill paid for it. We printed 70 issues. Then a friend hooked us up with a printing for the next three issues. They only cost us beer and paper and ink. We ran a 1000 copies of those and put them on cigarette machines all over New Orleans.

STEVE: Kinkos, of course. Bill paid for it. We printed 70 issues. Then a friend hooked us up with a printing for the next three issues. They only cost us beer and paper and ink. We ran a 1000 copies of those and put them on cigarette machines all over New Orleans.

MARK: One of the things that I’ve always found fascinating about Stupor is the blurriness of the line separating fact from fiction… You collect stories in bars, so there’s already, I’m sure, a bit of exaggeration and fogginess with regard to detail, but, on top of that, I think you’d agree that you kind of embellish here and there, in order to round out stories and give them a kind of narrative arc. And I think that’s kind of beautiful. You aren’t just collecting oral histories, but taking ideas from people and kind of collaborating with them in a way on these pieces of semi-fiction. Is that a fair assessment?

STEVE: That’s a pretty good description of the process. In the earlier issues (#5 — 9) there was less of that. The stories were more like quick sketches, like transcripts even. I recorded them on cassette or wrote them on napkins. Then I started working with them more. Fixing them, bringing the truth to the surface. I got real interested in that idea of what history is, what truth is, what is truthiness, and what is fiction, and creative non-fiction. Now, I usually get lumped in with creative non-fiction writers. I’d rather be known as the author of “true stories.” I like the phrase. It’s an oxymoron. I also like the idea that what I’m doing is taking a story that I heard and trying to distill a truth, to discover what’s happening in the telling and why it’s important and what it says about the teller. So in shaping the story, I’m forcing the truth to rise to surface.

MARK: Has anyone ever come back to you, after having read a story in Stupor based on something that they may have told you, upset about the way that you handled the material?

STEVE: That has happened a couple times. It was unpleasant. All the tellers in Stupor are anonymous, but apparently that’s not good enough. One time I wrote about it, detailing an incident, and later published it. It started when my friend told me that my zine sucked and that I had embarrassed him and I was full of shit. It was sort of a formative experience for me, grappling with the idea of what I was doing and why. Later I published my account of the incident, about getting called out by my friend. I kept expecting him to call me out again, but he never did. It appears in the issue “Hot Tasty Hell.” It ends like this, “I thought about it, but it didn’t seem like he owned that story. When he told it, when his breath made the words, he released it. He owned his memory of it. But my version of his truth, that was something different.”

MARK: So, in the process of fictionalizing stories, you think that you’re helping bring the truth to the surface… What do you mean by truth? In other words, it’s not necessarily the truth of the person who, over beers, helped you construct the crude foundation of the story… Are you suggesting that, though your process, you’re attempting to get at more universal truths that might not even be apparent to the person who first told you the story?

STEVE: I think it’s more absurd than that. In a way, what I’m doing is both claiming and denying authorship over the story. I’m putting myself in the teller’s shoes and writing it as if it was mine, then reconstructing the truth of it, and giving it back to the teller as if all the words had actually come from them. It’s weird sort of collaboration. I then publish under an anonymous heading, listing only the sex of the teller (Male or Female), and the city where the story takes place (Hamtramck). I’m not trying to prove anything. So I don’t like the idea of universal truths, because that seems to be connected to an agenda. I don’t have one. I just want to tell the story as well as I can. In writing and working with it, I’m trying to create a context that makes it real. I’m using details to establish place and to help define who the teller is. These elements rebuild a truth around it. If the teller doesn’t come off as a real person, then I’ve messed it up. I write each one until it feels completely true. Maybe truer than truth.

MARK: What makes a good story? Or, more to the point, what makes a story Stupor-worthy?

MARK: What makes a good story? Or, more to the point, what makes a story Stupor-worthy?

STEVE: People do surprising things all the time. Weird things. Human nature is flawed sometimes hilariously so. Stupor stories have an edge. They are raw but are not without humor or tragedy. They are worth retelling, at least that’s how I feel about them.

MARK: Having done this for almost 20 years now, what, if anything, have you learned about humanity?

STEVE: There’s all kinds out there and everybody wants something. Maybe it’s just another drink, or to win a small jackpot on the Keno, or maybe it’s got something to do with their spouse or even the gal on the stool at the end of the bar. Everybody makes mistakes. I like people that behave badly. They have the best stories.

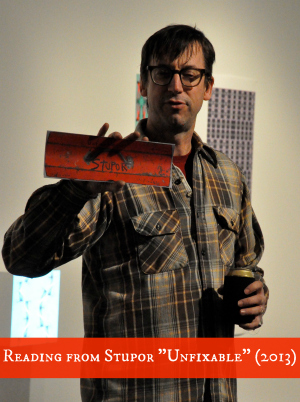

MARK: How many issues of Stupor have now been published? And are there plans afoot for another issue in the near future?

STEVE: I just counted 36 issues. I quit numbering them after issue 9. There never was a 10. I started slapping titles on them instead of numbers. So my newest issue, Stupor: Office Zombies is set for release January 10, 2014. I’ve been working on it with Detroit artists Steve and Dorota Coy, who go by the name the Hygienic Dress League. Their work is all about branding a fake corporation. So this Stupor is all office stories. I’m waiting now for an order of gold metallic paper. Yeah, this one is gold plated. I’m going to be reading it at the Work gallery in Detroit at 8:00 PM.

MARK: At 8:00 PM tonight, or on January 10?

STEVE: 8:00 PM, Friday, January 10.

MARK: A couple years ago, you released a bound collection containing some of your favorite stories. How’d that come about?

STEVE: I got a grant from the Kresge Foundation. They paid for the book.

MARK: Was it $10,000? I can’t recall the specifics?

STEVE: It was close to that.

MARK: What do you think the folks at Kresge liked about Stupor? Why, in other words, did you get the grant, and not someone, say, painting murals in Detroit?

STEVE: There was a group of judges for their Fellowship program. Four of them I think. I was only competing against other writers. I’d say my chances were pretty slim, being a zine writer. I guess I had a good application. That was for the big cash, the $25k. The grant for the book was a separate, project-based grant. All of the Kresge fellows were asked to submit ideas for projects and the funding needed to accomplish it. So the book was my project.

MARK: So you got $25,000 for the Kresge Fellowship, and then another $10,000 on top of that for the book project? …What did the fellowship entail?

STEVE: You’ve got it right. What an avalanche of dough! It all came at a good time too because of course I was broke and living off credit cards more than income. Basically it kept me afloat, during a hard time. As far as the requirements of the fellowship go, they were pretty loose. I think I had to agree to stay in the city for another year and keep writing. I didn’t have plans to leave, so it was easy.

MARK: How’d you select what to include? Did you know, going in, what kind of piece that you wanted to create, or did it evolve over time, as you sat with the material, considering it in its entirety?

STEVE: The book contains 14 full issues of Stupor that I published mostly between 2007 and 2011. I wanted to include all the work I’d done with artists, but pared it down just a little. It’s really a great collection. There’s over 100 stories in there, and the artwork is done by many of Detroit’s most recognized artists. So it’s a cool way to connect with their work as well.

MARK: How’d it sell?

STEVE: It did pretty good, especially at the beginning. I still have boxes in my office though. That’s the breaks for self-publishers.

MARK: Assuming people read this and want to buy a copy, what’s the best way for them to do that?

STEVE: Go to my website and buy it there. There’s a couple other issues for purchase there too.

MARK: You’ve been making use of Kickstarter quite a bit lately? What’s that experience been like?

MARK: You’ve been making use of Kickstarter quite a bit lately? What’s that experience been like?

STEVE: I’ve done it twice. Both times were successful. It’s a good platform, especially if you use it as a pre-sale or marketing tool. I liked making the videos. Even though I raised less money, I think the video in my second campaign was more effective than the first because my collaborating artist Jessica Frelinghuysen was into it. I wanted it to promote her work as well as mine. So we filmed it in her studio. Kickstarter is cool, but there are only so many times you can ask your friends for money. And sending out 100 mailings for the different reward levels is a real task. I’m relieved not to be doing it for my next issue. That one is in black and white, and I’ve got a resource for printing that won’t cost too much. So I’m shelling out the dough myself and hoping to sell enough to break even.

MARK: Do you ever find stories too troubling to include?

STEVE: Yeah, that’s happened a couple times. I still have the stories but they’re pretty tough to read, but who knows, maybe one day I’ll work back into them, and decide to publish them anyway.

MARK: Care to elaborate on what it was that kept you from publishing those particular stories? What was it that crossed the line?

STEVE: I’m not interested in stories that have strong racist, sexist or hate stance, or really any stance at all. Those stories I didn’t publish were crime related, from the victim’s side. They made me feel sort of sick. I don’t want people to feel that way when they read Stupor.

MARK: What’s the best thing to come from Stupor?

STEVE: I’d say the best thing about Stupor is that it gave me a platform and a voice, an audience too. I guess that’s not so different from what any zine writer might say. So maybe that’s universal. Working with artists has also been a huge great thing. Once I started collaborating, Stupor became more of a community effort. The artists made it so. At the same time they add this great visual element. They broaden my audience to include their audience. Plus I love art and the thought process behind making it. So it’s cool to be involved with the arts, even if I’m coming at it from a sort of slant position.

MARK: Anything you would have done differently?

STEVE: I wish I had better distribution. I’m sure there’s ways to make that happen. It used to be easier back in the 90s to disto. But then, as you know, a lot of them flaked out or went belly up.

MARK: Every so often, when Linette teachers her zine class at EMU, she has you come in and talk with the students about your experience with Stupor. I’m just curious what you’ve taken away from those discussions.

STEVE: Each time it was a learning experience for me too. It forced me to talk about Stupor critically and explain myself. So it stretched my brain. Also each time I got a little more comfortable with what I was doing. That probably made the classes better too. I don’t know if it’s obvious through this interview but there has been a real evolution of Stupor. It’s changed a ton from when I first started. Going to Linette’s class inspired me also to keep going, to push forward and rethink what I was doing. That coupled with those early Shadow Art Fairs that you put together gave me a reason to make when I felt like my audience had dwindled.

MARK: Any advice for people who might be thinking of starting a zine of their own?

STEVE: Do it. Make it. Try. See what happens.

STEVE: Do it. Make it. Try. See what happens.

MARK: What’s the best story you’ve ever been told?

STEVE: Recently I talked to a guy whose wife had just died. He was really happy, almost elated, like he’d won some jackpot. He told me the whole story. She had a heart attack and his daughter found her all blue on the floor. It was weird. I couldn’t tell if he was in shock, or if he was actually really glad. And if he was glad then, wow, that’s twisted! Either way, I got a great weird vibe from him. So far I’ve just sketched out his story, but I haven’t written it yet. To answer your question, though, I don’t have a favorite. Every story is my favorite. They mesh together. It’s more about the process of collecting and telling and writing it and discovering the truth of it that I most enjoy. Some go better than others. I’m not sure yet how I’ll handle this story of the dead wife. But I plan on spending some time with it. Working it and forcing the truth to surface.

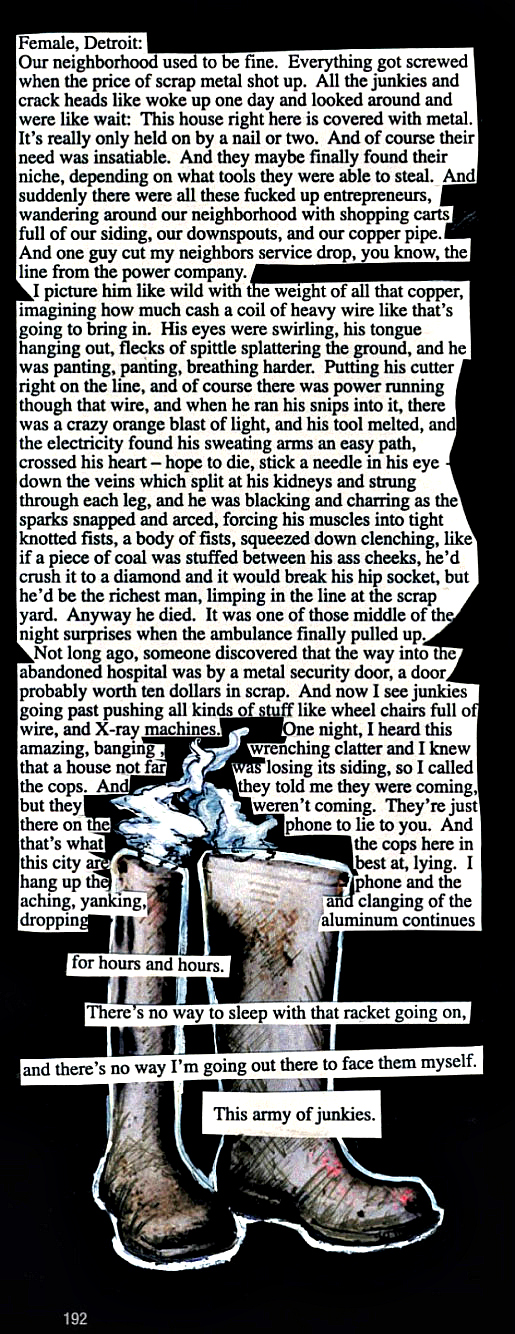

UPDATE: Here, for those of you who have never seen a copy of Stupor, is an excerpt from the issue “Math of Marriage.” The layout is by artist Clinton Snider.

[If you like what you’ve read above and want more, be sure to check the other interviews in the History of Zines series.]